Input Oddities

Published 2015-05-11

This is part 1 of a series called "Windows 95 Style Guidelines You've Probably Never Heard Of".

Windows 95, when it came out, was revolutionary, at least compared to the mess that was Windows 3.1 anyways. Along with the new concepts of a "desktop" and "window icons" and a "close button" were a understandably hefty style guideline. After all, if you're trying to go for "easy to use" and "consistent", it's best to make sure everyone else knows how to follow suit.

For the record, I'm specifically talking about the style guide at this link here, from February 1995, if you want to browse through that. It's worth a read, especially considering that I'm not planning on covering the design philosophies of the Windows team, which are pretty interesting.

This particular article is about weird interface oddities you've probably never though about. Not all of them are that odd, and not all of them even exist today, but they're things to think about.

Scrolling when Dragging (pg. 77)

This is probably something you take for granted, but the window scrolls when you move around content within it. And trust me, it certainly does not do that automatically. In fact, there's a formula that programs use to calculate how fast to scroll in any direction:

"To calculate the velocity, sum the distance between the points [of the mouse's position before and after] in each adjacent sample and divide the total by the sum of the time elapsed between samples. Distance is the absolute value of the difference between the x and y locations, or (abs(x1 - x2) + abs(y1 - y2)). Multiply this by 1024 and divide it by the elapsed time to produce the velocity."

This is noteworthy because a frustrating amount of programs only seem to want to scroll at a set speed that is simply far, far too slow half the time. In fact, it seems the only time where this is really done right is when you do the middle-click scroll. And it's not like you'd even have to program it yourself, as the OS provides built-in support for automatic scrolling. This is a minor thing that adds a lot to the feel of an application.

It's worth noting that it uses that weird formula instead of the typical Cartesian distance formula with square roots and all that due to computation speed issues. It's also worth noting that Windows 95 was released at a time where a floating point processor was still considered optional, much like airbags and ABS brakes were once considered optional in cars. Obviously, because it's the 21st century, you could probably get away with doing the more accurate math.

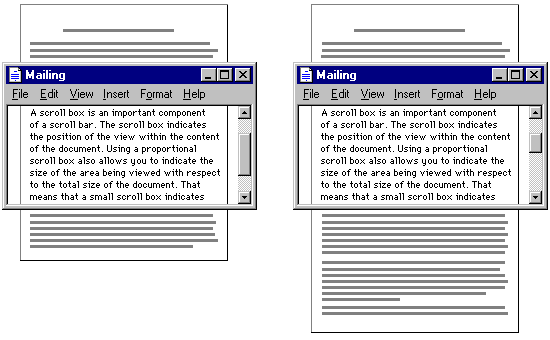

Proportional Scrollboxes (Pg. 98)

Another one of those things you never think about. There is, and has always been, a scrollbox to the right of content. You drag up on the scrollbox and the content goes up and vice versa. The entire scrollbar is supposed to represent the entire document. And, for the first time ever, Windows 95 scaled the shaft to be proportional with the document. No, seriously, this is huge. For the first time you could quickly tell the approximate size of the document, and precisely where you were on it.

The Shaft (Pg. 99)

The "background" of the scrollbar (named the "shaft") is actually clickable element. If you click on the shaft once, it moves the content a distance equal to the height of the visible on-screen space, with a little overlap. This is equivalent to the Pg. Up and Pg. Down keys most the time. Now, if you hold on the shaft, the auto-repeat feature kicks in, which causes it to page-up/down infinitely. Except not, because the scrollbox comes along and intercepts your mouse pointer, making it stop scrolling. It's a simple but efficiently genius idea, if you ask me.

The Scroll Lock Key (Pg. 102)

Yeah, that key. The key that's been sitting there collecting dust since forever. You've probably prodded that key, saw the light come on, and then realized that it seemed to do nothing. As it turned out it did do something. "When the SCROLL LOCK key is toggled on and the user presses a navigation key, [like Pg. Up/Down, arrows, etc] the view scrolls without affecting the cursor or selection." You probably thought it some old MS-DOS holdover, didn't you? Turns out that this whole time it was serving a very legitimate purpose. You can scroll up real quick to check something and then go back typing exactly where you were. Of course, you could do this with the scrollbar or scroll wheel as well, but for those keyboard power-users it's a nice feature. Unfortunately Microsoft seems to have axed this feature, as just trying it in Windows 7 did nothing. Darn shame too, I totally would have used that all the time.

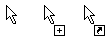

Different Pointers for Different Drag Operations (pg. 79)

Dragging and dropping in an application can preform a totally different action depending on the context. For example, in Windows Explorer dragging a file to the same drive moves, but dragging to another drive copies. It is often confusing when it does what, especially with unfamiliar programs. As it turns out they came up with a solution.

The blank pointer is supposed to symbolize moving, the [+] copying, and the shortcut icon OLE linking. This makes things a lot easier when it comes to determining what, exactly, you're even doing. This actually does still work does still work in modern Windows, however it is one of those things you never really think about.

While I'm talking about the difference between copying and moving, there's some neat tricks it has as well. Holding Ctrl and dragging does the opposite of the default action (copies if it is supposed to move and vice-versa) and dragging with the right mouse button pops up a menu asking you what action you want to take with the file.

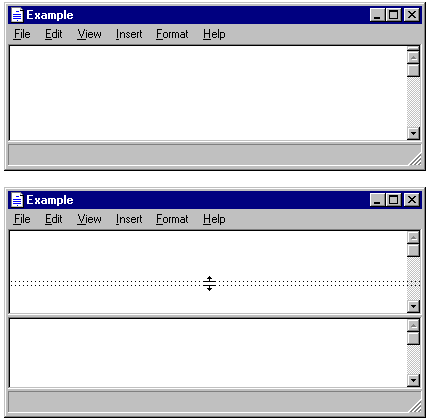

Split Boxes (Pg. 104)

A neat

feature of some applications is the ability to view documents side-by-side.

It's useful for viewing different parts of the same file, or possibly even two

different files, although this probably isn't the most optimal way to

accomplish that. Split boxes are a weird lost feature that make this ability

more obvious. To signify that a window can be split, a small box is placed

above the top scroll arrow. Dragging down from this splits the window into two.

Double-clicking on it splits it at a default location. And split boxes don't

have to disappear when you use them, allowing for multiple splits. It's a

really neat idea, but it was probably scrapped because it's functionality

wasn't obvious at first glance.

A neat

feature of some applications is the ability to view documents side-by-side.

It's useful for viewing different parts of the same file, or possibly even two

different files, although this probably isn't the most optimal way to

accomplish that. Split boxes are a weird lost feature that make this ability

more obvious. To signify that a window can be split, a small box is placed

above the top scroll arrow. Dragging down from this splits the window into two.

Double-clicking on it splits it at a default location. And split boxes don't

have to disappear when you use them, allowing for multiple splits. It's a

really neat idea, but it was probably scrapped because it's functionality

wasn't obvious at first glance.

Pen Input

Oh yeah. Windows 95 supported touchscreens. With handwriting-to-text and everything. It was really though out, to say the least. A good portion of the style manual is littered with pen-specific notes. It's, well, insane to say the least. Makes you wonder why they never took off back then. I'd assume it's because it was on the costly side, but then again light pens were around for years before that. Food for thought.